|

I was fortunate to be able to implement what is known in the parlance as a "course-based undergraduate research experience (CURE)" this spring in my upper-division plant biology class. Students added more than 275 research-grade observations to iNaturalist, contributed to a restoration research project by planting seedlings in a number of experimental plots, and carried out a significant field- and laboratory-based project collecting data on leaf thermal tolerances among native plant species in our coastal scrub community. We had an incredible partner in this endeavor in the form of Irvine Ranch Conservancy, which provided tremendous access, mentorship, and truly made it a memorable and deeply meaningful experience for our students. The work is described in a new article in the Fullerton Observer.

0 Comments

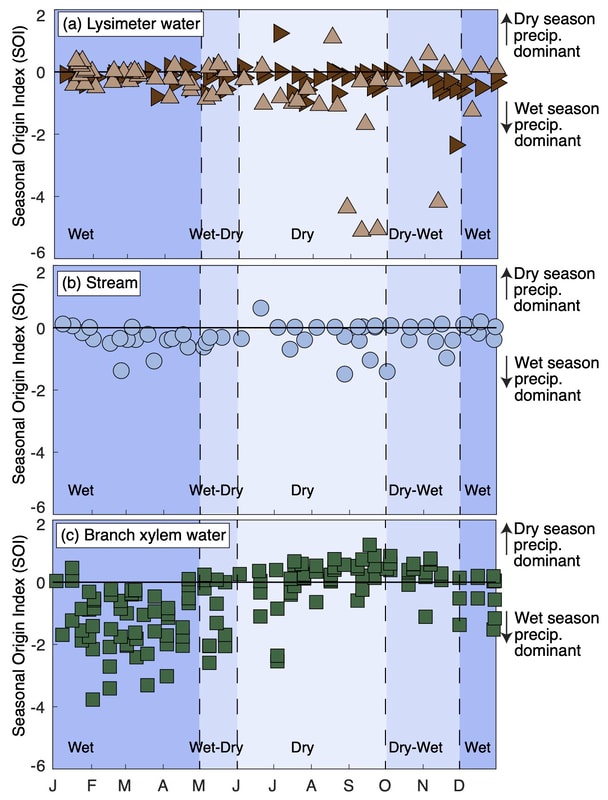

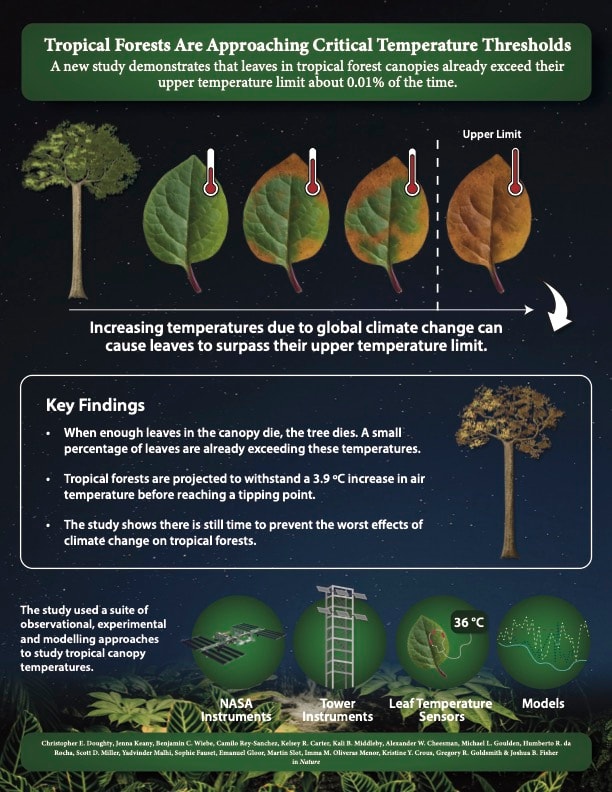

A new paper, led by Dr. Emily Burt during her doctoral work with Josh West (USC), describes the seasonal origins and ages of water moving through the cloud forests near Wayqecha Biological Station in the Andes mountains of Peru. While our group has been working hard to use the seasonal origin index (SOI) developed by Dr. Scott Allen (University of Nevada Reno to understand the spatial variation in tree and stream water sources (Allen et al. 2019 in HESS), this new paper applies SOI to study temporal variation in tree, soil lysimeter, and stream waters. Moreover, it applies the calculation of young water fractions, developed by our collaborator James Kirchner (ETH Zurich; Kirchner 2016 in HESS), to provide real depth of understanding with respect to how water is moving through this remarkable ecosystem. Perhaps the most striking result is that in this very wet system, we observe that plants are taking up wet-season precipitation during the wet season and dry-season precipitation during the dry season. This is a real contrast to what we have observed in the temperate forests of Switzerland (Goldsmith et al. 2022 in GRL) to date and adds a nice new piece to the puzzle: Burt, E. I., Goldsmith, G. R., Cruz-de Hoyos, R. M., Ccahuana Quispe, A. J., and West, A. J.: The seasonal origins and ages of water provisioning streams and trees in a tropical montane cloud forest, Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci., 27, 4173–4186, https://doi.org/10.5194/hess-27-4173-2023, 2023. Abstract: Determining the sources of water provisioning streams, soils, and vegetation can provide important insights into the water that sustains critical ecosystem functions now and how those functions may be expected to respond given projected changes in the global hydrologic cycle. We developed multi-year time series of water isotope ratios (δ18O and δ2H) based on twice-monthly collections of precipitation, lysimeter, and tree branch xylem waters from a seasonally dry tropical montane cloud forest in the southeastern Andes mountains of Peru. We then used this information to determine indices of the seasonal origins, the young water fractions (Fyw), and the new water fractions (Fnew) of soil, stream, and tree water. There was no evidence for intra-annual variation in the seasonal origins of stream water and lysimeter water from 1 m depth, both of which were predominantly comprised of wet-season precipitation even during the dry seasons. However, branch xylem waters demonstrated an intra-annual shift in seasonal origin: xylem waters were comprised of wet-season precipitation during the wet season and dry-season precipitation during the dry season. The young water fractions of lysimeter (< 15 %) and stream (5 %) waters were lower than the young water fraction (37 %) in branch xylem waters. The new water fraction (an indicator of water ≤ 2 weeks old in this study) was estimated to be 12 % for branch xylem waters, while there was no significant evidence for new water in stream or lysimeter waters from 1 m depth. Our results indicate that the source of water for trees in this system varied seasonally, such that recent precipitation may be more immediately taken up by shallow tree roots. In comparison, the source of water for soils and streams did not vary seasonally, such that precipitation may mix and reside in soils and take longer to transit into the stream. Our insights into the seasonal origins and ages of water in soils, streams, and vegetation in this humid tropical montane cloud forest add to understanding of the mechanisms that govern the partitioning of water moving through different ecosystems. There are some good reasons to believe that no two tropical forests necessarily have the same canopy temperatures. And no two trees within a tropical forest necessarily have the same canopy temperatures. In fact, it is not necessarily true that every leaf in a given tree has the same temperature. The challenge is trying to measure all of those leaves, particularly when one begins to think about forests as large as the Amazon or the Congo basin.

Our interest in leaf temperature is because we know that when leaves reach a certain temperature, their photosynthetic machinery breaks down. We have known about these critical temperature thresholds for more than 150 years. Our new study in Nature is an effort to establish how close tropical forest canopies are to these limits. One of the most remarkable aspects of this study was the methods we were able to use to determine canopy leaf temperatures. It is remarkable that we can observe the temperature of the world tropical forests from an instrument on the International Space Station orbiting 400 km above Earth’s surface and traveling nearly 29,000 km per hour. It is equally remarkable to imagine the painstaking efforts made by my colleagues to measure the temperatures of individual leaves in the canopy by hand. We need both the ground- and satellite-based observations to understand the temperatures of tropical forest canopies. For leaf temperatures, it is not the averages that are important. It’s the extremes. And this study shows that there are times and places where tropical forest leaves are surpassing their critical temperature thresholds at least once per season. Moreover, we show that when we experimentally warm air temperatures, we often observe leaf temperatures that are higher than that of air temperature. These higher air temperatures exceed the limits of cooling that the leaves can achieve and so the leaves accumulate excess heat. It's a non-linear effect between increasing air and increasing leaf temperatures. The results do not indicate that reaching a tipping point for tropical forests is fait accompli. We still hold in our power the ability to conserve these places that are so critically important for carbon, water and biodiversity. Doughty, C.E., Keany, J.M., Wiebe, B.C. et al. Tropical forests are approaching critical temperature thresholds. Nature (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06391-z Dr. Emily Burt, a postdoctoral research associate on our team, has just published a preprint (for open discussion) in Hydrology and Earth Systems Science. Emily carries out a suite of interesting analyses on water isotopes in order to explore metrics of the seasonal origins and ages of water in streams, soils, and trees of a tropical montane cloud forest in the eastern Andes Mountains of Peru: read the preprint.

Photo Credit: Drew Fulton (Canopy in the Clouds) Greg Goldsmith will serve as the national program chair for the Ecological Society of America's annual meeting in 2024. The meeting will be held in Long Beach, California and is expected to attract more than 3000 ecologists from all over the world. Goldsmith is an early career fellow of the ESA.

We have published a new German-language summary of our research on processes and patterns of forest water use in the Swiss Journal of Forestry. We have been working on the project now for seven years and we've begun to generate an interesting and diverse set of results:

Goldsmith, G.R., S.T. Allen, S. Braun, R.T.W. Siegwolf, & J.W. Kirchner. 2022. Climatic influences on summer use of winter precipitation by trees. Geophysical Research Letters 49: e2022GL098323 4 Allen, S.T., J. von Freyberg, M. Weiler, G.R. Goldsmith & J.W. Kirchner. 2019. The seasonal origins of streamwater in Switzerland. Geophysical Research Letters 46: 1-28. Allen, S.T., S. Jasechko, W.R. Berghuijs, J.M. Welker, G.R. Goldsmith & J.W. Kirchner. 2019. Global sinusoidal seasonality in precipitation isotopes. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences 23: 3423-3436. Allen, S.T., J.W. Kirchner, S. Braun, R.T.W. Siegwolf, & G.R. Goldsmith. 2019. Seasonal origins of water used by trees. Hydrology and Earth Systems Sciences 23: 1199-1210. G.R Goldsmith, S.T. Allen, S. Braun, N. Engbersen, C. Romero González-Quijano, J.W. Kirchner, & R.T.W. Siegwolf. 2019. Spatial variation in throughfall, soil and plant water isotopes in a temperate forest. Ecohydrology 12: e2059 Allen, S.T., J.W. Kirchner, & G.R. Goldsmith. 2018. Predicting spatial patterns in precipitation isotope (18-O and 2-H) seasonality using sinusoidal isoscapes. Geophysical Research Letters 45: 4859-4868.

I have a new editorial out in the Editor's Blog of Science. You can read some additional thoughts in the Twitter Feed below.

Andrew Felton, who is currently a USDA-NIFA postdoctoral fellow studying rangeland sensitivity to drought, will leave us this fall to join the faculty in the Department of Land Resources and Environmental Sciences at Montana State University.

His lab will focus on understanding how climate change impacts the functioning of western US dryland and agricultural systems, with an emphasis on the consequences of ongoing intensification of the water cycle (e.g., drought). He'll be looking for graduate students and postdoctoral associates - what a great opportunity. We are so excited for Andrew and could not be more excited to continue collaborating far in the future! From the International Space Station, An Unprecedented Look At Plant Resilience To Drought4/15/2022 Orange, Calif. — A new instrument on the International Space Station (ISS) is helping scientists understand the inner workings of plant life here on Earth by showing how different plants balance the tradeoffs between growth and water use. A team of scientists from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and Chapman University has now undertaken a major global study of these tradeoffs, described as plant water-use efficiency, among 9 different plant types in 11 ecosystems around the world using tens of millions of observations.

In this first-of-its kind study, “Convergence in water use efficiency within plant functional types across contrasting climates,” published on April 14th in the prestigious journal Nature Plants, the authors found that plants of the same type (such as deciduous broadleaf and evergreen needleleaf trees, tall or low shrubs, herbs and non-herbaceous grasses, etc.) often had very similar water-use efficiency regardless of where they grew. Interestingly, the results indicate that it is the type of plants, rather than the climate in which they are growing, that dictates the water-use efficiency. The results also indicate that plant types with longer lifespans, such as shrubs and trees, have higher water-use efficiency than plant types like grasses, which have shorter lifespans. These findings provide important insights into how global climate change will shape the future of plant communities and the ecosystem services they provide. Plants use and lose water when they take up carbon dioxide to photosynthesize and grow. Plant species capable of growing more while using less water may be more resilient to the increasing frequency, intensity and duration of drought events projected to occur with global climate change. The study also reveals connections in how environmental conditions can shape current and future plant community characteristics, key for understanding the future of plant biodiversity. Knowing how different plant types optimize the tradeoffs between growth and water use, the so-called plant water-use efficiency, can inform plans to mitigate and adapt to a warmer and drier future. This type of analysis was enabled by the data collected from the ISS instrument, known as ECOSTRESS, which provides the most detailed temperature images of Earth’s surface ever acquired from space. These temperature images indicate evapotranspiration and photosynthesis rates. Previously, the low-resolution of available data and disagreements among different land surface models led to wildly varying measurements of water-use efficiency. “ECOSTRESS revealed patterns that we could not observe with previous satellite instruments and that would be impossible to measure on the ground,” said lead JPL author Ms. Savannah Cooley. For instance, using ECOSTRESS images from the Brazilian Amazon, the study demonstrated significant variation in water-use efficiency by plant type over the scale of just a few miles of seemingly similar tropical rainforest, as well as abrupt changes where forests had been converted to pasture. The data originate from ECOSTRESS, the ECOsystem Spaceborne Thermal Radiometer Experiment on Space Station, a mission launched by NASA in 2018 to provide information on global land surface temperature at unprecedented spatial and temporal resolutions. ECOSTRESS was built by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) and launched into orbit aboard a SpaceX Dragon cargo spacecraft lifted by a Falcon 9 rocket. ECOSTRESS now sends images at a resolution less than that of a football field every 2-3 days. “ECOSTRESS is remarkable in that it allows us to determine plant water use nearly anywhere on Earth at spatial scales that were unthinkable just a few years ago, all from an instrument that is traveling more than 17,000 miles per hour more than 250 miles above us,” noted study co-author Dr. Joshua Fisher. The new study was led by Ms. Savannah Cooley, a graduate student at Columbia University and scientist at JPL, in collaboration with Dr. Joshua Fisher and Dr. Gregory Goldsmith at Chapman University. Fisher is a Presidential Fellow of Ecosystem Science in Schmid College of Science and Technology; he was the Science Lead for ECOSTRESS while at JPL prior to joining Chapman. Fisher is the first faculty member in Chapman University’s history to be named a highly cited researcher by Clarivate, placing him in the top 1% of researchers globally. Goldsmith is an Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences and Director of the Grand Challenges Initiative; he is a member of NASA’s ECOSTRESS Science and Applications Team. Measurements provided by ECOSTRESS are also useful for detecting wildfires, urban heat waves, volcanic activity, and a number of other applications. ### The title of the paper is “Convergence in water use efficiency within plant functional types across contrasting climates,” and is available online at: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41477-022-01131-z. Support was provided by the ECOSTRESS mission and by the NASA Research Opportunities in Space and Earth Science grant # 80NSSC20K0216. Among the great accomplishments of folks in the lab, we're sending Cami Acosta to Sanford Research in Sioux Falls, South Dakota for an NSF Research Experience for Undergraduates this summer. She'll be joining the Surendran Lab to study kidney development and disease! Can't wait to see the results!

Recent graduate Sydni Au Hoy has been offered a COMET (Clinical Observation and Medical Transcription Fellowship) at Stanford Medicine. A great next step on her pathway to becoming a doctor! |

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed